Ninth Sunday after Pentecost, August 10, 2014

Rev. Fr. Andrew Stephen Damick

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, one God. Amen.

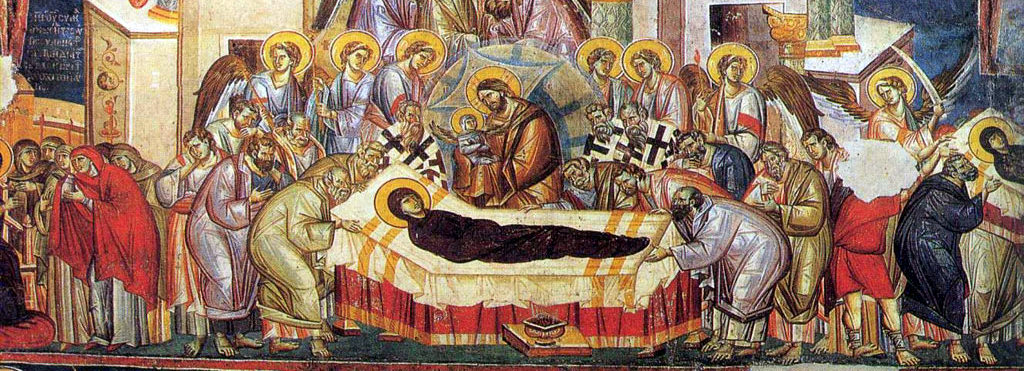

We are now most of the way through the Dormition Fast, those first fourteen days in August when we gather with the Apostles at the bedside of the holy Theotokos and Ever-Virgin Mary, the Mother of our Lord, as she prepares to pass from this earthly life into the age that is to come. We are in this time of waiting and keeping vigil for the moment when God chooses for her to bring her soul to Himself.

This image is quite an immediately potent one for me right now, because, as you know, my own mother Sandy is at this moment making the same preparation to pass through death into life. You know that I do not usually speak about my own life in sermons, because a good sermon is not about the preacher. But perhaps there are some things that I can share with you from this experience that may be of some benefit as we prepare for the Feast of the Dormition and most especially as we prepare ourselves for our own passage through death into life everlasting.

When we heard that my mother’s diagnosis of aggressive brain cancer had been confirmed, as you know, we rushed to be with her, because we had no idea how much longer she would be awake. She wanted to see all her children and grandchildren, so Kh. Nicole and I stuffed our three rambunctious younguns in the back seat of our little Prius and set out for the more than 1,800 mile journey to Colorado. It took us three very long days to get there, with overnight stops in Indiana and Kansas, and you can only imagine what kinds of sounds proceeded from the back seat.

When we finally arrived, I dropped Nicole and our two boys off at the place where we were staying, and I took our daughter to the hospital to see my mother, where she was in hospice. My father and my mother’s two sisters were there. I had asked my father if it would be okay for me to pray for my mom in the way that we are used to praying for the sick in the Orthodox Church, and so when I got there, I greeted her and asked her if she would like me to pray for her. I prayed a few brief prayers for her and anointed her with oil from St. Thekla Monastery here in Pennsylvania that Mother Justina gave me to bring to Colorado, since I could not give her holy unction.

And I have to imagine that, even though anointing with oil for the sick is something not much practiced in the variety of Christianity practiced by most of my family, they at least have read James 5:14: “Is anyone among you sick? Let him call for the elders of the church, and let them pray over him, anointing him with oil in the name of the Lord.”

The next morning, my mother asked for our immediate family to be with her, and my father, brother and sister were all there. We spoke with her for a while, and then each of us spoke with her alone. I told her what she meant to me and asked her to forgive me for all the trouble I had given her in life, especially as a young man.

The next evening, my mother called us all together and spoke with each of us quite directly, ending by praying for each of us. It was rather intense and dramatic and clearly took a great effort, and I think most of my family expected that she would pass away almost immediately, though eventually she just fell asleep again.

Over the week that followed, Kh. Nicole, the kids and I visited my mom every day. Most of the time I would just sit with her and read to her from the Scriptures, but we also talked about various little things. I wished I could stay with her until the time finally came, but the doctors are saying that it could still be a couple months, and there are things we need to do during that time here in Pennsylvania. So we’re back for now, at least until the time comes for me to return for the funeral. And now we wait and watch.

A couple months ago, my mother wrote in a passage my dad shared with me this week that she felt that she was always waiting on God for something. And in a life that for her was defined by a lot of moving from one place to another, from one project to another, the shape of life can become defined by waiting. The next thing is always on the horizon. The next moment will be coming.

All this was perhaps prefigured for her when she was born, because the doctors told my grandmother that my newborn mother was going to die, so they might as well take her home and just wait for that to happen. But of course that’s not what happened. My grandmother accidentally overcooked some baby formula, which then happened to be just the right thing for my mother to swallow and keep down and begin to be nourished.

And my family now finds itself waiting for the earthly end of that life God chose to save so many years ago. We are waiting for my mother to die. We don’t want it to happen, but it’s happening. We don’t know when it will be happening. But we still have to wait. And we also watch. And those who are there with her in Colorado are waiting and watching most closely. And the rest of us keep our vigil from afar.

Sometimes in life, waiting can be overwhelming. We don’t know what will happen next. And waiting is often accompanied by worrying. My grandmother must have been worried for my baby mother. My family is worried now for her: Will she feel too much pain? Will she remain herself up until the end? Will there be someone in the room with her when she passes into the next life?

Sometimes, waiting even for what is likely the inevitable can be too much. I’ve seen more than one person post on my dad’s Facebook profile that they’re praying for miraculous healing for my mom. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course. We pray for healing all the time, and we should pray for healing. But when I saw those comments, I thought about what it would have been like if one of the Apostles had approached the deathbed of the Mother of the Lord and said to her, “We’re praying for a miracle for you!” It just doesn’t make sense.

While I know my mother would not compare herself to any of the great saints of the Bible except to hope she could be like them, her own passage through death into life is very similar right now to that of the Virgin. She is at peace with it. She even said when they brought her home, “I know why I’m here.” Almost every word she speaks to people is to tell them about God’s blessings in her life, about His love which has been more than she could ever imagine. She kept saying to me, “The love of God is beyond measure.”

No, I don’t want my mom to die. She’s only 61. It should have been years from now. My dad should have his beloved wife into his old age. My mom should live to see her great-grandchildren. But that’s not what’s happening. And when the Virgin Mary passed through death, I am sure that there was great sorrow at her passing, too. No one wanted her to die. No one wanted this woman who had held the very God of the universe within her womb to leave us all alone. Think of what was being lost! Think of that unique human experience of God passing from this world!

And think of what it must be like to be waiting for that, waiting in uncertainty for the inevitable.

In remembering the passing from this life of her grandmother, my mother wrote this: “Waiting can be hard, but I learned that it is in the waiting that we get to spend time with God in His presence. Grandma’s presence was a wonderful place to be. I never really knew why when I was young. I know now. She loved me so much! God’s presence is so wonderful because He loves me so much!”

And so we wait. But we are Christians, and so we wait while redeeming the time. Whether we are waiting for something good to happen, for something bad to happen, or even just waiting for the completion of our own days here on this earth and our passage through death to life, we do not wait without hope. We do not wait without action. We wait with expectation. We wait with love to be in the presence of the God Who loves us, the God Whose presence is indeed full of wonder. Our waiting is a waiting that is happy to be here for as long as we can. We are here to be with God. And that is enough.

To God therefore be all glory, honor and worship, to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit, now and ever, and unto ages of ages. Amen.