The hieromartyr’s name is Joseph the son of George Moses the son of Mouhana Al-Haddad, known as the father Joseph Mouhana Al-Haddad. Usually he takes pleasure in introducing himself as a person whose origin is from Beirut, and his homeland is Damascus, and his faith is Orthodox. His father left Beirut in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, establishing himself in Damascus; there he worked weaving fabric, married and begot three sons: Moses, Abraham and Joseph. His family’s origin goes back to the Ghassanids; his ancestors moved to the Lebanese village of Al-Firzul in the sixteenth century, and from there to Biskinta, in Mount Lebanon, then to Beirut.

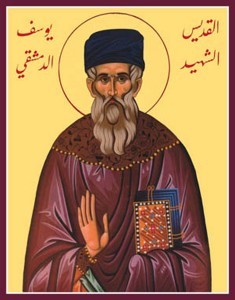

His biographers describe Joseph as a medium sized priest, with white complexion, dignified appearance, large forehead, sharp-witted eyes, and bushy beard, in which the gray hair has spread its lines, until it resembles the rays of the sun at daybreak.

He was born in May 1793, to a poor but pious family. At an early age he obtained some education, so he became acquainted with Arabic and some Greek. Unable to afford tuition, his father decided to halt his education in favor of putting him to work in the silk industry. His desire for knowledge, however, was not quenched by poverty and destitution, so he decided to find a solution. He started working all day long and teaching himself at night; necessity created a self-made person. Most likely, his older brother Moses, who was a well-educated writer and a well-versed person in the Arabic language, motivated him to have such a desire toward knowledge. Moses had a small library at home, upon which Joseph embarked studying, but sadly Moses departed this life at the age of twenty-five; it is said that he died because he overexerted himself in study. This ordeal had an ambivalent impact on Joseph’s parents concerning Joseph’s longing toward books. The torch of knowledge, however, continued to burn in Joseph’s heart.

Reaching the age of fourteen, the young man started to read his brother’s books, but he was frustrated because he could comprehend just a little from what he was reading. Unsuccessful, he was not disheartened, and his determination increased tremendously. His question was: “Was not the author of these books a human being like me; why do I not comprehend them? I should grasp their meaning.”

Then, he studied under a Damascene Muslim elder, Mouhamad Al-Attar, who was one of the greatest scholars of his age; he learned from him Arabic, logic, the art of debate and right reasoning. He discontinued his studies, however, because tuition and the cost of books overburdened his father; he was obliged to go back to his old lifestyle; working all day long, and teaching himself at night.

At this point, it is important to mention that schooling then was coupled with spirituality and theology. We should not forget that the Bible was the most important textbook.

Joseph dedicated his evenings wholeheartedly to study the Torah, the Psalms and the New Testament, comparing the Greek text of the Septuagint with the Arabic translation, until he gained mastery in translation to and from Greek. His knowledge was not limited to the Greek language, but he was able to memorize a greater portion of the Bible.

He persisted in seizing every opportunity to gain more education with great yearning. Joseph studied theology and history under Maître George Shahadeh Sabagh. He then started teaching from his home; he learned Hebrew under one of his Jewish students.

His tenacious endeavor kindled the fear of his parents, so they tried to dissuade him from learning and teaching. for fear that he might face the same fate of his brother. Unsuccessful in their efforts, they tried another solution. They gave him in marriage to a Damascene young woman whose name was Mariam Al-Kourshi, while he was still nineteen years of age (1812). Marriage, however, did not turn him away from his pursuit of knowledge; his biography tells us that even at the night of his wedding he persisted in reading and learning.

Becoming aware of his honorable reputation, the parish in Damascus requested Patriarch Seraphim (1813-1823) to ordain him as their pastor. Since the Patriarch had a high admiration for him, he ordained him a deacon, then a priest within one week while he was still twenty-four years old (1817). When his successor, Patriarch Methodios (1824-1850), became acquainted with his fervor, godliness, knowledge and intrepidity, he elevated him to an archpriest, and gave him the title: Great Oikonomos.

Taking a great interest in preaching for many years from the pulpit of Patriarchal Cathedral (Al-Mariamieh), he achieved excellent result in his preaching. Some people regarded him as the successor of Chrysostom.

Naaman Kasatly praised him in his book The Luxuriant Garden as a creative preacher. At the end of the nineteenth century, i.e., thirty-nine years after his death, Amin Kairala mentioned in his book The Fragrant Odor that the elderly were still reiterating some of his sermons.

The echo of his sermons were still reverberating until the beginning of the twentieth century; Habib Al-zaiat a Melkite writer mentioned that he was renowned among the Orthodox Arabs by his knowledge and preaching.

In his sermons he was distinguished by his proofs and his convincing and irrefutable answers. According to Issa Iskander Al-Maloouf, he had a quite voice that could be heard from a distance. People used to listen to his words with longing and enjoyment and to emulate his advice and keep his commandments.

Along with his sermons, he was diligent in comforting the heartbroken, in consoling the grief-stricken, in helping the destitute and in strengthening the feeble. In 1848, when the yellow fever spread in Damascus, Father Joseph manifested a great fervor in ministering to the sick, and in burying the dead, without being troubled by the possibility of catching this infectious fever, because he had profound faith in God. Although he lost one of his children by this contagious disease, he was tireless in going his pastoral duty. His fervor, his steadfastness and his compassion increased. He was highly respected by the Damascene people; they was in him the image of Saint Paul who said: “We are afflicted in every way, but not crushed; perplexed by not driven to despair, persecuted, but not forsaken; struck down, but not destroyed; always carrying in the body the death of Jesus Christ, so that the life of Jesus may also be made visible in our bodies” (2 Cor. 4:8-10).

Among his multifarious endeavors, he succeeded in turning the people away from many unorthodox traditions during betrothals, weddings and funerals. As he was competent in building up souls, he was competent in building churches. In 1845 he restored the church of Saint Nicholas, which was next to the Patriarchal cathedral, though it was consumed by fire during the horrible events of 1860.

We do not know precisely who established the Patriarchal school in Damascus, nor when it was established. It is confirmed that the school became so associated in the nineteenth century with the name of Father Joseph, until it became known as his school.

When he took charge of the school in 1836, he brought together its students with his own students. Then he spared no effort to develop it, by appointing a board of administration and gave the teachers regular salaries, until it attracted students from all

Syria and Lebanon.

Father Joseph’s concern was to educate the minds of Orthodox young men, and to “prepare them for priesthood and to serve the flock in a useful way.” The expenses of education were covered by the faithful and by the Patriarchate.

His vision was to make interest in theological studies increase. In 1852, during the patriarchate of Hierotheos (1850-1885), Father Joseph took the initiative to open a department of theological studies, striving to elevate it to the level of the other theological seminaries in the Orthodox world. Twelve students were enrolled in it, and all of them became bishops in the Church. His martyrdom in 1860 put an end to his dream, however, which aimed to establish the department on solid foundation.

He breathed into his students the spirit of peace and success which can be found among the saints, until this godly spirit spread like a chain beyond his students and graduates to reach all their acquaintances, colleagues and friends. Thus, his teaching became widespread, and his education bore the fruit of righteousness.

It is mentioned that Father Joseph was for a period of time one of the teachers at Balamand Seminary, between 1833 and 1840.

One of the main characteristics of this archpriest and teacher was his poverty. Some sources mention that his ministry to the Church was without payment. One of the Russian scholars said that he had no income from teaching school; he used to earn his living from the labor of his children. Money never tempted him.

Because of his intact reputation, Cyril II, Patriarch of Jerusalem (1845-1872), asked him to teach Arabic at the clerical school in Jerusalem (Al-Mousalabah). When he declined, the Patriarch offered him a tempting salary, twenty-five pounds, in addition to an apartment and priestly wages. He declined in spite of his need. He said that “I was called to serve the parish in Damascus; He who called me will satisfy me.”

He was a true worshiper, fervent in his faith, exceedingly patient, righteous, meek, quite, humble, compassionate, and a friendly person; he hated to talk about himself, he felt embarrassed by the praise of others, not knowing how to answer them.

He was wise and patient in his pastoral care; he used to confute the scholars by speaking their language and to convince the simple people by using their language. When a few simple-minded people left the Church for an insignificant reason, Patriarch Methodios asked him to bring them back. After he met them he did not manifest any resentment for their behavior, but he treated them with kindness, showing them some small icons; they came back repentant after he had touched their hearts.

As a scholar, he was the professor among the teachers, the star of the East, and a working intellectual. Many non-Orthodox contemporary people testify that he was one of the great Christian scholars of his epoch. “In the Orthodox Church, he was a very distinctive person in his knowledge; there was no one like him, except George Lian.” As a churchman, he was considered a great theologian, a pride of Orthodoxy, a hieromartyr and an example in righteousness and godliness.

Those are the characteristics of archpriest Joseph the Damascene: he is one of God’s people.

We have no knowledge of the size of his library, because it either burst into flames or was looted during the calamities of 1860, when he received the crown of martyrdom. His nephew, Joseph Abraham Al-Haddad, mentioned that Father Joseph possessed about 1,827 books (or probably 2,827 books) in the year 1840.

His writings were numerous. He compared the book of Psalms, the Breviary, the Liturgikon, and the book of Epistles to their original Greek. He translated into Arabic the catechetical book of Epistles to their original Greek. He translated into Arabic the catechetical book of Philaret, Metropolitan of Moscow. In copying the manuscripts, he used to compare them with other manuscripts and correct them; his versions were accurate like “the unforged silver coin.” He edited the translation of deacon Abdallah Al-Fedal Al-Antaki of Saint Basil’s book on Genesis as well as thirty sermons of Saint Gregory the Theologian. With the following colophon, he used to finish the manuscripts: “This book was copied from an old manuscript, and compared to it completely.” And with his seal and signature he used to imprint it. All the Orthodox printing offices, like Saint George in Beirut, the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, the Arabic printing houses in Russia relied on Father Joseph in editing, comparing, and proof-reading their books. In theology, literature and scholarships his seal was a seal of trust. In translating from Greek to Arabic, and from Arabic to Greek, he joined efforts with Yanni Papadopoulos. He made a great contribution in editing the Arabic translation of the Bible, which is known as the Edition of London. All the drafts, prepared by Mr. Fares Al-Shidiak and Mr. Lee, had to be corrected by Father Joseph, by comparing them to the Greek and Hebrew languages.

In his literary contribution, he showed in his stamina faithfulness and correctness; his complaint was always the misreading of printing houses. We have no knowledge about his own writings, except for a few articles. Apparently, he did not consider himself worthy to keep pace with the great Fathers of the Church. He confined himself to translating, editing, and presenting their writings to the faithful as a pure, intact and unblemished heritage.

During the epoch of Father Joseph, the problem of dealing with the Melkite (they had been part of the Orthodox Church until recently) was the most difficult and most painful impediments which faced the children of the Orthodox faith. At that time, all the endeavors were directed toward getting the schismatics back to the Church. In dealing with this issue, some followed the way of political and administrative pressure, others followed the way of reaching mutual agreement. Father Joseph belongs to the second group.

He hated violence, and he did not concede to have connections with the Ottoman Empire to knock down and oppress the Melkites. This is an unprofitable style; it strengthens separation, and weakens unity.

The measure of his success in this is unknown to us, but what happened in 1857 and the following years show that his vision was more correct that others. In that year, when the Melkite Patriarch Clement forced the Western calendar upon his church, many took offense at this procedure, and decided to go back to the mother Church. A group of them, under the leadership of Shibli Al-Demashki, George Anjouri, Joseph Fouraeig, Moses Al-Bahri, Sarkis Dibanah and Peter Al-Jahel, contacted Father Joseph, who embraced them, strengthened them and struggled to enlighten them for three consecutive years. He prefaced a book written by Shibli Al-Demashki about the protestations of this group. The title of the book was Christian Law is Far Above The Astrological Considerations; it was printed in the publishing house of the Holy Sepulcher in 1858. The size of the group started to grow rapidly, until it was said that had not the martyrdom of Father Joseph taken place during the massacre of 1860, he would have succeeded in bringing back the rest of the Melkites to the Orthodox faith.

Father Joseph had more than one confrontation with Protestants. The most important ones were in the cities of Hasbaia and Rashaia, then in the city of Damascus.

In the city of Hasbaia, the American Protestant missionaries had a great success through their school which they had established in that city. More than a hundred fifty persons converted to Protestantism, as a result of conflict between the Orthodox people in those two cities. As an envoy of Patriarch Methodios, Father Joseph was able to bring back some of the straggling sheep to the Orthodox fold. After he refuted the missionaries several times, he succeeded in restraining them.

In Damascus he strove in his pastoral care, preaching and guiding his people to the enlightenment and to fortify them against the circulating sects and heresies. It is mentioned that an English missionary, Grame, used to meet Father Joseph and discuss Biblical issues with him. Realizing that this missionary was perverting the answers given by Father Joseph on the questions raised, he asked him to send their questions in a written form. In the beginning they thought that they had confuted him, after he neglected to answer them. Whey they came in the beginning of Great Lent, he answered all their questions accurately, until they returned amazed by the correctness of his knowledge and research. It is said that as a consequence of that incident they ended their missionary campaign on the Orthodox congregation; their questions were for inquiry and not for debate.

Undoubtedly, Father Joseph was, in the nineteenth century, the greatest man of renaissance in the Antiochian Church. At that time, Antioch was in a pathetic situation. The schism of the Melkites [in 1724] led to very critical repercussions on different levels, especially on the pastoral level. The Protestant missionaries were very active and aggressive, while the Church was impotent and feeble, ignorant and poor. Starting from 1724, the [Orthodox] hierarchs were foreign to the land and to the struggle of its people. Antioch lived under custodianship, under the pretext that she was going to disintegrate gradually and become Catholic. In the name of Orthodoxy, both Constantinople and Jerusalem distributed among themselves the authority of appointing Antiochian bishops, trying to determine her destiny. At that time there were no competent priests and no pastoral care. The Antiochian Church could be described as a ship stricken by waves, and ready to

sink.

In the midst of those challenges and dangers, Father Joseph bloomed as a new godly branch, having a great fervor toward God and the Church of Christ in the land.

Then, renaissance started.

Father Joseph’s life, fervor, godliness, poverty, love of knowledge, persistent pastoral care, preaching, guidance, writings, translations, school and vigilance created a revivalistic atmosphere, motivated the spirits, moved the hearts, and strengthened determination. A new generation, a new thinking, and a new direction bloomed. “The bones came together, bone to its bone… and breath came into them, and they lived” (Ezekiel 37:7-10).

More than fifty Church leaders studied under him, and became as watchful as he was: Patriarch Meletios Al-Doumani (+1906), first indigenous patriarch since 1724; Gabriel Shatila, Metropolitan of Beirut and Lebanon (+1901); the great scholar Garasimos Yared (+1899), Metropolitan of Zahle, Saidnaia and Maloula; and his students were more than ten bishops, as well as a large number of priests, among them Archimandrite Athanasius Kaseer (+1863), founder of Balamand seminary; Father Speredon Sarouf (+1858), dean of the clerical school in Jerusalem and editor of the publications of Holy Sepulcher; Archpriest John Doumai (+1904), founder of the Arabic publishing house in Damascus; in addition to some renowned laymen such as Dimtiri Shahadeh, a pillar of

renaissance; Michael Klaila, administrator of the Patriarchal schools in Damascus; and

Dr. Michael Mashakah (+1888).

What he longed for was accomplished during his lifetime and after his death; oftentimes he repeated: “I planted the seed in the true vineyard of Christ, and I am waiting for the harvest.”

All these things can be explained in the statement of Metropolitan Gabriel Shatila: “The stars of Damascus are three: The Apostle Paul, John of Damascus, and Joseph Mouhana Al-Haddad.”

His life should be crowned with an ending equal to his godliness and great love, in which he would glorify God through his martyrdom.

On July 9, 1860, when the massacre in Damascus started, many Christians took refuge in the Patriarchal Cathedral (Al-Mariamieh); some came from the Lebanese cities of Hasbaia and Rashaia, where the massacre started and where killing took place. Others came from the villages around Damascus.

Following the tradition of the priests in Damascus, Father Joseph used to keep a communion kit in his house. During the massacre of 1860 he hid his communion kit under his sleeves, and went jumping from one roof to another toward the Cathedral. He spent the whole night strengthening and encouraging the Christians to face the situation, for the attackers can kill the body but cannot kill the soul (Matthew 10:28); the crowns of glory have been prepared for those who committed themselves to God through Jesus Christ. In relating to them the martyrdom of some saints, he called them to emulate their life.

On Tuesday morning, July 10, the persecutors belligerently attacked the Cathedral, robbing, killing and burning everything. Many martyrs were slaughtered, others went out on the streets and alleys; on of them was Father Joseph. As he walked on the streets, a religious scholar, who was one of the attackers, recognized Joseph, because the latter had confuted him in a debate between them. Seeing him he shouted, “This is the leader of Christians. If we kill him, we kill all the Christians!” When he heard these words, Father Joseph know that his end had come; he took out his communion kit, and partook of the body and blood of Jesus Christ. The persecutors attacked him with their hatchets, as if they were woodcutters, and disfigured his body. Binding his legs with ropes, they dragged him over the streets until he was dashed into pieces.

Although he died as a martyr, his life, his vigilance, and his sufferings were a witness of his holiness. By “becoming like Him in His death” (Phil. 3:10), he was crowned with His glory. He became an example to be emulated, and a blessing to be acquired, and an intercessor to our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, to Him be the glory forever. Amen.

Written by Archimandrite Touma Bitar

Abbot of St. Silouan the Athonite Monastery in Douma, Lebanon

(translated by the Very Rev. Michel Najim)

(source)

Further editing has been added for this website.